Type and Transcendence: Philippe Apeloig

by Caitlin Condell

The cerebral, meticulous posters of Philippe Apeloig have made him a graphic design luminary. He was the subject of a large career retrospective at the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris this past year, and Thames & Hudson published a hefty monograph, Typorama, documenting Apeloig’s creative output of the last 30 years. At a recent event at the Type Director’s Club of New York, enthusiastic designers packed the room, peppering the artist with questions. The Paris exhibition was similarly filled with young people, diligently sketching the posters on view—a phenomenon that design critic Steven Heller recalls last seeing… “never!” Apeloig’s designs are notable for recasting typography as a vibrant, even narrative domain; for their dynamic color sense; and in the case of his limited edition screenprints, for their elegant dance between art and design.

“I don’t think most people expect to encounter personal expression in graphic design. They view it as the art of communication and as a commercial art.” Though designers are charged by their clients to communicate a specific, predetermined content, Apeloig sees expressive potential in the tools used for the task. Typography, he says, can be “a strong artistic element, like color is for painters or metal might be for sculptors,” and can create an “emotional dimension.” Similarly, screenprint can push “designs beyond the industrial aspect and into a greater artistic dimension.”

Apeloig’s first serious encounter with screenprint was as a student in the early 1980s. At the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués and the École Supérieure Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris he received traditional training in typography, working with calligraphy, hand lettering and metal type. But he also experimented with printing, playing around with the colors and shifting the elements of his design in one-off screenprints. He is drawn to screenprint because “the colors are rich, powerful, strong and bright, which is ideal when you’re looking for strength and delicacy.” Of his early printerly experiments he says, “it was like painting with the silkscreen.”

After leaving school, Apeloig worked at the influential design firms of Wim Crouwel in the Netherlands and April Greiman in Los Angeles. Crouwel’s posters, such as Visuele Communicatie Nederland (1969) for the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, were innovative in their reliance on pure typography, rather than photographic or pictorial images. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles-based Greiman was breaking new ground with the use of computers in design. Though rooted in Swiss Modernism, Greiman’s work transgressed a strict interpretation of Modernist tenets. In her poster Your Turn My Turn (1983), “the typography appeared to be floating in space in an acrobatic fashion.” (Alice Morgaine, “Signs of Life,” in Typorama) Greiman encouraged Apeloig to embrace emerging technologies and break free from the orthodoxy of Swiss graphic design. Apeloig came away from these experiences with a firm understanding of the grid as a means of organization and of type as a realm of invention. (Ellen Lupton, “A is for Apeloig” in Typorama)

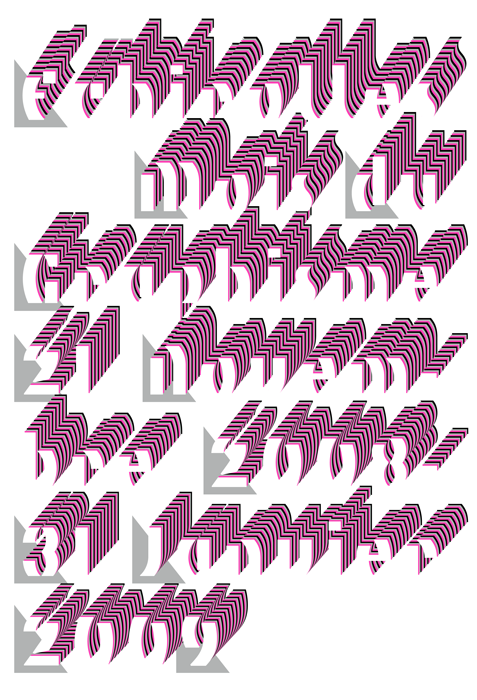

In 2006 the French library association (ABF) held a centennial conference organized around the theme of “the library tomorrow.” Brought in to establish the organization’s graphic identity, Apeloig sought to convey the idea of the library as a place of research, but also of community—something “much more than books.” He created a new typeface, ABF, whose rectangles, parallelograms and circular forms can be arranged to read as letters and numbers, but also as tables, chairs and bookcases. For ABF’s 2009 conference on library architecture, Apeloig created a variant of the font, setting the white letterforms within black boxes that divide the space of the poster and its text into cubicle-like formations.

Also in 2006, Apeloig designed the poster Le Havre (2006) for a competition commemorating the UNESCO designation of the French city as a World Heritage Site. Heavily bombed during World War II, Le Havre was rebuilt in part through the vision of the Modernist architect August Perret—a reconstruction notable for its unified integration of extant historic structures with modern, modular concrete construction. Apeloig’s entry took the city’s innovative architecture as its subject and used Perret’s conception of the city as a Gesamtkunstwerk as a framework. Graphic renditions of three of Perret’s standardized façades are overlaid, each in a primary color, recalling the vocabularies of Modernism and Constructivism. The layered façades generate secondary colors, while the letter shapes echo the windows in which they appear to sit. The design aligns Apeloig’s nuanced interpretation of the grid with Perret’s modular elegance. Apeloig was so pleased with the poster (it did not win the competition) that he produced it as a limited edition screenprint.

Designs that he feels are “good enough” Apeloig releases in screenprint editions of 30 to 40 impressions. These represent an ideal iteration—the poster equivalent of a director’s cut, stripped of the “visual pollution” of distracting sponsorship logos, printed on better paper and sometimes reprising a variant that had been rejected by the client. “My posters are really paintings that I never executed.”

Apeloig is scrupulous about the printing of these works. (He encourages his clients to consider the medium for commercial production whenever possible, though the economic advantages of offset lithography for large runs and digital print-on-demand for short runs mean that many of the commercial screenprinters with whom he has worked have closed or ceased screenprinting.) While printers used to prep the screens and send full proofs to the designer for review, printers now more commonly send only small color tests, so Apeloig often goes to the print shop (he currently works primarily with Lézard Graphique, near Strasbourg) to supervise the process. While screenprint allows the direct application of an unlimited range of inks and materials, including metallic and fluorescents, Apeloig tries to limit himself to two or three PMS Pantone colors in any given design.

Apeloig is conscious of the intertwining histories of art, commercial design and screenprint. The Typorama book methodically documents his designs beside the “high art” works that inspired them: paintings by Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso, dances by Rudolf von Laban and Barbara Morgan, and photographs by Constantin Brancusi, Eadweard Muybridge and Alex Jay. For the background of Yves Saint Laurent, a poster for the couturier’s retrospective exhibition at the Petit Palais in 2009, Apeloig used a detail of a photograph of Saint Laurent taken in the 1960s by Pierre Boulat and reproduced it through a large dot-screen, a conscious nod to the screenprints of Andy Warhol. For the famous YSL logo he chose to reproduce A. M. Cassandre’s original gouache drawing from 1961; and the poster’s palette echoes the primary colors of Saint Laurent’s most iconic dress, itself an homage to the paintings of Piet Mondrian.

In works such as this, typography works in tandem with the velvety texture and concentrated colors of screenprint. Vivo in Typo, designed for an exhibition of Apeloig’s own work in 2008, builds its giant letters and pulsating design from punctuation marks: periods, plus signs and dashes. Through manipulation of the order and spacing of these elements, the title “VIVO IN TYPO” emerges as if woven in a tapestry, an effect enhanced by the substantiality of the ink on the paper’s surface.

Such materiality is particularly conspicuous now, when, as Apeloig notes, we are “entering an era of dematerialization.” Today video screens occupy locations where posters used to hang: in train stations, subway cars, outside museums and theaters, in the street. But Apeloig does not bemoan the rise of the digital. “It brings so many possibilities… the attractiveness of dimension, movement, light and sound and all forms of interactivity.” For the Mois du Graphisme à Échirolles festival in France in 2008, Apeloig created an animation in which typographic layers build up and diminish to the rhythm of a piano piece by Maurice Ravel; the final frame resolves on the design of the poster. The shift to digital, Apeloig suggests, may open up a new future for the printed poster.

Caitlin Condell is the curatorial assistant in the Department of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York.

Type and Transcendence: Philippe Apeloig

Presse, 01.07.2014 www.artinprint.org/TypeAndTranscendence